First, man receives a heart from a genetically modified pig.

This breakthrough could one day lead to new supplies of animal organs for transplantation into human patients.

A 57-year-old man with life-threatening heart disease received a heart from a genetically engineered pig.

A revolutionary procedure that offers hope to hundreds of thousands of patients with failed organs.

This is the first successful transplant of a pig’s heart to a human being.

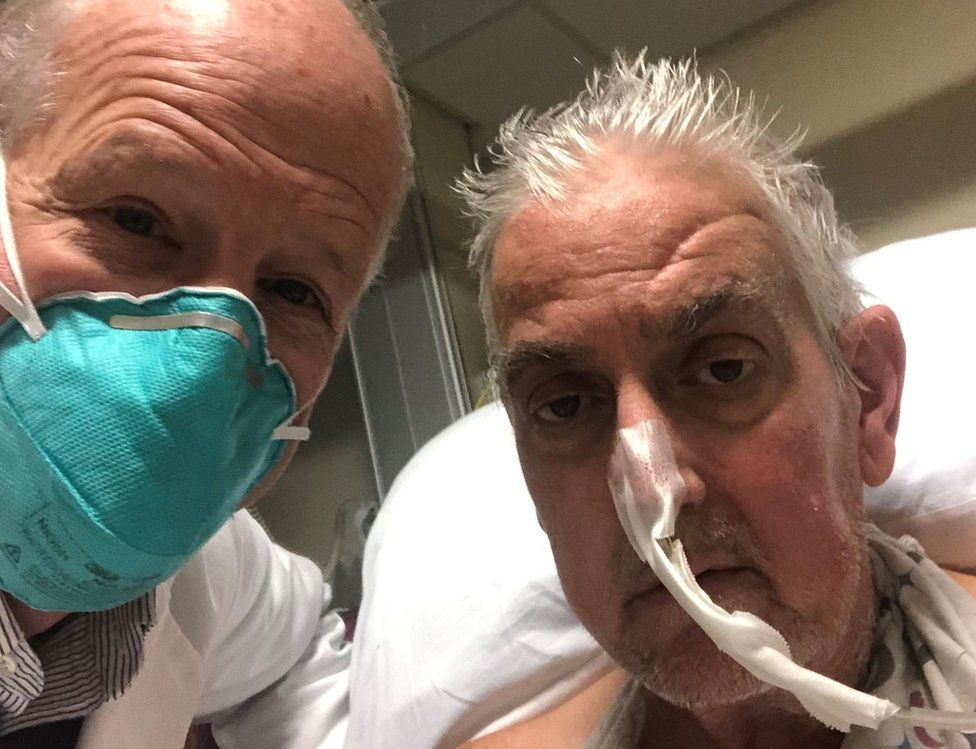

The eight-hour operation took place in Baltimore on Friday, and the patient, David Bennett Sr. of Maryland, was doing well on Monday, according to surgeons at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

“It creates the pulse, it creates the pressure, it’s his heart,” said Dr Bartley Griffith, director of the medical center’s heart transplant program, who performed the operation. “It works and it looks normal.

This has never been done before so we are delighted, but we do not know what tomorrow will bring us.

Last year, some 41,354 Americans received organ transplants, more than half of whom received kidneys, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, a nonprofit that coordinates the nation’s organ procurement efforts.

But there is a severe organ shortage, and about a dozen people on the lists die every day.

Some 3,817 Americans received replacement human donor hearts last year, more than ever before, but the potential demand is still higher.

Scientists have worked feverishly to develop pigs whose organs would not be rejected by the human body, research accelerated over the past decade by new gene editing and cloning technologies.

The heart transplant comes just months after surgeons in New York City successfully attached the kidney from a genetically engineered pig to a brain-dead person.

Researchers hope procedures like this will usher in a new era of medicine in the future, when replacement organs are no longer scarce for more than half a million Americans waiting for kidneys and others. organs.

“This is a watershed event,” said Dr David Klassen, chief medical officer of the United Network for Organ Sharing and transplant physician.

“Doors are starting to open that will lead, I think, to major changes in the way we deal with organ failure.

But he added that there were many hurdles to overcome before such a procedure could be widely applied, noting that organ rejection occurs even when a well-matched human donor kidney is transplanted.

Dr Klassen said “Events like these can be dramatized in the press, and it is important to keep a perspective,” “It takes a long time for therapy like this to mature. ”

Mr Bennett decided to bet on the experimental treatment because he would have died without a new heart, exhausted other treatments and was too sick to qualify for a human donor heart, family members and doctors have said. doctors.

Prognosis

His prognosis is uncertain. Mr Bennett is still hooked up to a heart-lung bypass machine, which kept him alive before the operation, but that’s not unusual for a new heart transplant recipient, experts said.

The new heart is working and already doing most of the work, and its doctors said it could be removed from the machine on Tuesday.

Mr Bennett is being closely watched for signs that his body is rejecting the new organ, but the critical first 48 hours have passed without incident.

It is also monitored for infections, including porcine retrovirus, a porcine virus that can be transmitted to humans, although the risk is considered low.

“It was either die or do this transplant,” Bennett said before the operation, according to officials at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

“I want to live. I know it’s a hit in the dark, but it’s my last choice.

Dr Griffith said he first broached the experimental treatment in mid-December, in a conversation ‘Memorable’ and ‘quite strange’.

“I said,” We can’t give you a human heart; you don’t qualify.

But maybe we can use one from an animal, a pig, “Dr Griffith remembers.” It has never been done before, but we think we can do it. “” I was not sure he understood me, “added Dr Griffith.” Then he said, “Well, am I going to crack it?”

Xenotransplantation

”Xenotransplantation, the process of grafting or transplanting organs or tissues from animals to humans, has a long history. to use the blood and skin of animals date back hundreds of years.

In the 1960s, some human patients had chimpanzee kidneys transplanted, but the longest life span of a recipient was nine months.

In 1983, a baboon heart was transplanted into a baby known as Baby Fae, but she died 20 days later. Pigs offer advantages over primates for obtaining organs because they are easier to raise and reach adult human size in six months.

Pig heart valves are routinely transplanted into humans, and some patients with diabetes have been given pig pancreatic cells.

Pigskin has also been used as a temporary graft for burn patients. Two newer technologies — gene editing and cloning — have made genetically modified pig organs less likely to be rejected by humans.

Pig hearts have been successfully transplanted into baboons by Dr. Muhammad Mohiuddin, a professor of surgery at the University of Maryland School of Medicine who, along with Dr. Griffith established the cardiac xenotransplantation program and is its scientific director.

But safety concerns and fear of triggering a dangerous immune response that could be life-threatening prevented its use in humans until recently.

How the heart was modified?

Dr. Jay Fishman, the associate director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Transplant Center, said using pig organs opens up the opportunity to perform genetic manipulations, the time to perform better infectious disease screening and the possibility of a new organ when the patient needs it.

The heart that is in Mr. Bennett was transplanted from a genetically altered pig supplied by Revvivicor, a regenerative medicine company based in Blacksburg, Virginia.

The pig had 10 genetic modifications. Four genes were turned off or inactivated, including one encoding a molecule that triggers an aggressive human rejection response.

A growth gene was also inactivated to prevent the pig’s heart from continuing to grow after it was implanted, said Dr. Mohiuddin, who along with Dr. Griffith did much of the research prior to the transplant.

In addition, six human genes were inserted into the donor pig’s genome — modifications intended to make the pig organs more tolerable to the human immune system.

The team used a new experimental drug, developed in part by Dr. Mohiuddin and made by Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals to suppress the immune system and prevent rejection.

It also used a new machine perfusion device to preserve the pig’s heart until surgery.

The Food and Drug Administration worked intensively towards the end of the year and finally gave the transplant surgeons emergency clearance for the surgery on New Year’s Eve. The surgeons encountered some unexpected twists and turns. “The anatomy was a bit squirrel-like, and we had a few ‘uh-oh’ moments and had to do some clever plastic surgery to get everything to fit,” said Dr. Griffith.

When the team removed the clamp restricting blood flow to the organ, the heart “fired straight up” and “started squeezing the animal’s heart.”

When Mr. Bennett first told his son, David Bennett Jr., about the upcoming transplant, he was stunned. “At first I didn’t believe him,” said the younger Mr. Bennett, who lives in Raleigh, N.C. lives.

“He’d been in the hospital for a month or more and I knew that delirium could set in.

I thought, there’s no way that’s going to happen.” He said his father had a pig valve inserted about ten years ago, and he thought his father may have been confused.

But after a while, Mr. Bennett said, “I realized, ‘Man, he’s telling the truth and not going crazy. And he could be the first ever.'”

Source: – Newyork Times